Enchaining the Bridgers: An old guy’s epic adventure

- charlesjromeo

- Jul 9, 2024

- 12 min read

Updated: Feb 26, 2025

Enchaining: def, to bind or hold as if with chains.

Ever since I moved to Bozeman in June 2020, I have found the prospect of enchaining the Bridger Range enticing. The desire to walk through and bag the peaks of the northern part of the range was the main driving force. When I’d be out in the valley, I’d regularly glance in the direction of the northern peaks and was enchanted by their beauty.

I have completed four Ridge Runs, put on by the Big Sky Wind Drinkers, so I have had something of a view of the Bridgers from Sacajawea south; racers, however, spend much of their time looking at their feet so as to not trip over the infinity of sharp rocks that are the Ridge Trail; our views, as such, are cramped. Backpacking through the range would provide the opportunity to take it all in.

The definition of enchaining that I found in the dictionary, doesn't really capture the spirit of what I am doing; it sounds more like a medevil torture. No, what I wanted to engage in is a fully modern form of torture: aka epic adventure. The idea of enchaining a mountain range first came to my attention when I read an article by Mark Jenkins in Outside magazine about 20 years ago. In that story, him and a buddy moved light and fast climbing the highest peaks of the Bighorn Range in two days and ended up back where they began. My plan was also to be light and fast, but the Bridgers are a linear range, not well suited to enchaining, so I had to get creative.

The solution I arrived at was to bike by roads on the west side of the range from the M Trailhead at the south end of the range to Flathead Pass, at the north end, on my mountain bike sticking to dirt roads to the extent possible. Then, have some as of yet unspecified person drive to Flathead Pass with my pack, exchange my bike for my pack and start hiking south.

My goal was to start on the Summer Solstice and I had a lot to do to get things ready once the snow started to melt off the peaks. There is no water up on the ridge and once I was up there, I had no intention of coming down until I got the M Trailhead, so I had to bring water up. I had to get in better biking shape and wanted to explore as much of the course as possible, Flathead Pass Road in particular. I discovered the west side of the pass road to be a steep rugged jeep trail. Jeep drivers love it, but sections clearly double as creek bed during spring melt and were too steep and rocky to ride; a mile or more of hike-a-bike would have to be part of the plan.

My neighbor Phil volunteered to shuttle my pack and bike, and wanted to hike up to the ridge above Flathead Pass with me to place a gallon of water. I knew that I was placing my first jug too far north, but not knowing the area, I didn’t have a good feel for where else I might place it, and there was also the point that I wanted to see this part of the trek. I had to make sure I could get through this section, because once I donned my pack and Phil drove away, I didn’t have a good backup option for getting out of there.

The route to the ridge was steep, but we linked together a set of meadows and made quick work of getting up there. My first impression was that the northern ridge was gentle. I was disabused of this impression when I reached the top of the first rise to the south and found a gnarly mix of limestone walls and trees to be negotiated. After a short rough section things again improved. I carried the water beyond the first small peak heading south and made my way partway down toward a section that looked curious. My first impression, was that I was going to have to work through a forest of limestone monoliths. It looked challenging, but it also might be fun. Ed Anacker Peak, the first big peak in the northern section of the range, rose beyond the monoliths. I stashed the water, took some pictures and we headed home.

A section of ridge above Flathead Pass; Ed Anacker Peak and the first glimpse of the Monolith Forest

Running the Old Gabe 30K on June 15th, another Wind Drinkers race, interrupted my preparations. I returned home from the race to find Terry in bed with a nasty case of Covid. That stopped preparations until the Paxlovid took effect and I was sure I didn’t have Covid. With the big snowstorm that dumped about a foot in the upper mountains on June 18th, the solstice start idea drew its dying breath. Once the snow cleared, I put a gallon up on Saddle Peak but I still had two last preparations to make. I had tried to get up North Cottonwood Canyon two weeks earlier, but snowmelt and deep snow turned me back. It was my first realistic exit if I had to get off the ridge, so I wanted to get up there to see the canyon, and look for routes down if it came to that. I did a 10.6 mile run up in there on Tuesday, June 25th. On Wednesday the 26th, I biked and hiked up Brackett Creek to Ross Pass where I would place my third and last gallon of water. I was finally set, and with the exception of some midday thunderstorms, the forecast looked good for a start the next day.

Thunderstorms, especially heavy ones like we had that day, make dirt roads muddy. I dealt with a veneer of mud the whole way north to Flathead Pass Road in addition to a steady headwind. When I turned onto the pass road, the mud was no longer just a veneer. At first, I managed to find enough gravel to ride on to keep moving forward, but then the soil composition must have changed. I stopped before a section of deep ruts and slick mud. I didn’t even try riding through it. I slipped so much I could barely walk, and those knobby bike tires picked up so much mud that my back wheel stopped turning. I cleaned out enough mud to get things moving again, then my chain fell off. Fix. Start. Stop. Repeat. I got through that section, made it a bit further. More mud. Repeat. I discovered that carbon fiber bikes lose the quality of lightness they are valued for when they are encased in globs of mud.

I reached the steep rocky climb. I was tired from a lack of rest and from the ride north in that headwind and my trials in the mud. I walked a lot more than I did on the test climb. I finally got near the pass and Phil hiked down to meet me. The first piece of the enchainment was complete. The plan was to camp, enjoy a fire with an evening and breakfast of hot meals, then well rested and with a full belly, I would dash off on my light fast venture.

It didn’t work out that way. I awoke at 2:15 am to a howling wind. It buffeted my tent the rest of the night and I knew that if it did not relent, I was not going to start hiking in the morning. The plan was to have an adventure, the plan did not include a death wish. We packed up all our gear and drove home.

I settled in at home and looked for another weather window. I decided that the bike part of the enchainment was complete, so the focus was now on a 2-day window to backpack the range. The 2nd and 3rd of July looked promising. Phil was good to go. The plan was set, until he had a mishap while doing a house project Monday afternoon and ended up in the ER. The weather ended up not being as good as I expected. Lots of clouds and rain in the mountains. It would have sucked to be up there. Phil, in retrospect, had taken one for the team. On Wednesday, Phil called, saying that he was doing better, he couldn’t camp, but he could drop me off at the pass when I was ready to go. Thursday was the 4th of July, that was out, but the forecast for Friday and Saturday looked good. He picked me up at 7 am Friday morning, I started my trek at 8:30.

I don’t like being out in the mountains alone hiking and running, but at my age there are few options for raging partners, at least in those disciplines. So I headed into the mountains alone, trekking poles in my hands, bear spray at the ready, confident that I would have cell phone access once on the ridge.

My kit weighed 21.5 pounds plus 3.5 liters of water, 28 pounds in total at the start. I had removed everything from my pack that wasn’t absolutely essential—my backpacking pillow was essential, hot food and coffee were not. I made the ridge in an hour, found the gallon I had stashed less than a mile later, then considered the Monolith Forest with nervous anticipation.

A wall greeted me as I entered the forest. My only choice was to drop down to get around it. The scree field was steep and slick. Progress was slow. I made it down and around this wall then had to work past obstacle after obstacle. I found myself thinking in terms of 100-foot increments—after I hike the 100 feet I can see, I’ll figure out where to go next. It continued like this for more than a mile, more than an hour. It was beautiful, I took lots of pictures.

I began to equate being in that forest with being on the sharp-end of the rope when leading a climb. I’ve led sport routes in a gym, but I’ve never been an outdoor climber. I imagine that being on the sharp-end of a trad route involves a lot of self-control to keep your emotions in check. This had that flavor. I just had to carefully consider my options at each decision point and keep going. Freaking out would lead to disaster.

3 views from inside the Monolith Forest, one view looking back from the shoulder of Ed Anacker Peak

At one point I worked my way along a wall up to the ridge and found no way forward just a steep drop down the east face of the mountains. I turned around started hiking downhill and found myself at a new decision point. The wall had a gap before it ended. I went around the gap but the scree field around the end of the wall was so steep I feared sliding down it. I headed back and looked through the gap. A five-foot cliff that I would have to downclimb with somewhat flatter terrain below. I chose the cliff. Problem was I couldn’t do the downclimb with my poles or with my pack on. I hesitated, then I dropped my poles down. They stayed where I dropped them. Good. I took off my pack hoping to get it to land flush on the back so that it too would stay, but I couldn’t quite get far enough out over the cliff to guarantee it would land right. It didn’t and I watched it roll out of sight. Suddenly the trip was at risk. I got down the cliff and raced down the hill, knowing that it might have rolled 1,000 feet or more before stopping and my gear might be splayed everywhere and water containers breached. About 150 feet down I saw it lodged against a tree. The outside pockets, which are made of a lightweight stretchy screen material, were shredded, but the main pack still had its integrity and the neither my water bladder nor the gallon jug had failed. I picked up the pack, started climbing, and went around the monolith. It was the last one. In minutes I was on the ridge and steadily climbing Ed Anacker Peak.

The wind kicked up as I climbed, not howling, but a steady 10-20 mph. I made the peak in short order, and the next higher, but unnamed, peak also fell quickly. I was now at the northern corner of North Cottonwood Basin. The ridge made a sharp turn east and dipped down before coming back around and rising back up. This drop in the ridge provided my first view of the line of northern Bridger peaks to my south. It was stunning. Frasier Peak was first in line. It was a beautiful thrust faulted lizard head that jutting out above the rest of the ridge. It looked steep; I hoped it was climbable.

The lineup: Frasier, Hardscrable, Pomp, Sacajawea and Naya-Nuki; Frasier Peak's lizard head

I tagged the two small peaks around the back of North Cottonwood and then started climbing a rocky ridge that brought me around to Frasier. There was no trail up Frasier, but there was a faint animal, maybe human, trail across the lizard’s neck. I hiked it until I found a point to drop my pack, carefully this time, and I climbed up through steep loose scree and tagged the peak.

The view north from Frasier Peak; Frasier Lake

Hardscrabble was next in line. It looked steep and rocky from the north, but as I came around its aspect become gentler. I climbed the not too rough southwest ridge and descended the downright gentle south face and was on my way to Pomp Peak. I made my way around to the south side of Pomp where I knew there was a trail, dropped my pack and I climbed Pomp behind a group of women and their dogs. I was back in civilization now, so to speak. I dropped off Pomp, headed down to Sacajawea Pass, ducked below the pass to get out of the wind, and took my first break of the day. I had gone 8.4 miles in 8 hours, 20 minutes. The hardest part of the adventure was now behind me.

To finish the day, I still needed to hike up Sacajawea and Naya-Nuki; I tagged the knuckle of rock that stands between them for good measure, then dropped down to the Foothills Trail and made my way to Ross Pass. I got there at 8:30 pm, in time to set up camp and chat up two guys who were also camped there. It was nice to have folks to talk to after a long day of being alone. It had been a hard day. I slept well.

I awoke the next morning, downed a caffeinated energy gel and some nuts and headed up Ross Peak. It was the longest and toughest climb in the range, lots of steep loose scree, then a fun hike along the ridge in search of the highest rock tower. AllTrails rates it a Class 2 climb, I beg to differ. There are sections that require both hands and feet, a Class 3 rating to me seems more accurate.

Views north and south from Ross Peak

I broke camp and started south again. I was on the Ridge Trail. As I hiked, I noticed a few things about the trail. It’s a gnarly blend of sharp rocks, roots, and steps up and down. It’s not that there aren’t smooth sections with beds of pine needles, but they are the exception. After the race, we all humble brag about how bad the trail is. Seeing it at a slower pace it was even worse than I thought. It is a testament to everyone’s training that so few are bloodied by the course.

The other thing I noticed is that more sections of trail than I was aware must have had some level of planning behind them. I mean, the trail was still rough in what I believe were planned sections, but I just cannot imagine those sections resulting from the patter of thousands of feet randomly finding their way through the wildlands surrounding the ridge. The face below Bridger Peak is a prime example and there are others.

Once I reached Pomp Peak, I started seeing other people. I was so excited that a few times I blurted out what I was accomplishing. That generally generated a disinterested grunt in response. But the ridge is generally the land of day hikers and trail runners. Some folks approached me when they saw the pack and inquired as to what I was up to. Then my excited banter generated an excited response.

The last conversation I had was an odd one. I was just north of Baldy and a hiker approached me heading north. He asked, “Where you coming from, I’m probably going there.” I looked at him. He was carrying a half full 20-ounce Coke and had on a little kid’s school pack with not much in it.

“Flathead Pass, but that Coke is not going to get you there.”

“Oh then I’ll probably go to Truman Gulch.”

I looked at him quizzically, “Do you know how to get there?”

That question generated a blank stare. I suggested he turn around and head back. He wouldn’t hear of it. I suggested he do the Baldy loop trail so that he didn’t have to hike back the same way he came, but he was determined to continue. I finally pointed out Saddle Peak, and told him about the climbers’ trail down to the Foothills Trail and pointed at a section of trail down in Middle Cottonwood Canyon. It was 5:15. He figured that he would make it out around dark. I was less sure that he would make it out at all, but I wished him luck and suggested he call for a ride before he dropped off Saddle as he would lose service in the canyon and it was a long walk to anywhere from there. I hope he made it out.

The end of backpacking trips are never particularly fun, especially trips that we characterize as ‘epics.’ They are supposed to hurt, and by the time I started down Baldy my feet had had enough. I struggled my way forward down that 4,000-foot descent. I sat down on the bench at the M Trailhead right around 8:30 pm; my epic was at an end 36 hours after it began. Two sets of folks who approached me at the trailhead wanted to know where I had come from. I started telling my tale and forgot all about my feet.

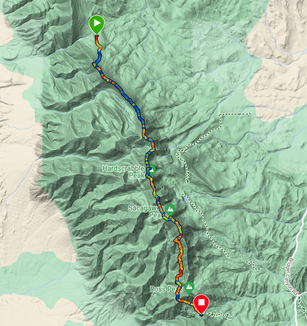

The route and Garmin stats:

Bike Route: 30.44 miles, 3579 feet climbed, 1568 feet descended

Backpacking Day 1: 14.11 miles, 6929 feet climbed, 6158 feet descended

Backpacking Day 2: 14.23 miles, 5151 feet climbed, 7733 feet descended

The author takes a selfie on Saddle Peak

Comments